Human between birth and puberty

"Children" and "Childhood" redirect here. For other uses, see Child (disambiguation), Children (disambiguation), and Childhood (disambiguation).

International children in traditional clothing at Liberty Weekend

International children in traditional clothing at Liberty Weekend

A child (pl. children) is a human being between the stages of birth and puberty,[1][2] or between the developmental period of infancy and puberty.[3] The term may also refer to an unborn human being.[4][5] In English-speaking countries, the legal definition of child generally refers to a minor, in this case as a person younger than the local age of majority (there are exceptions like, for example, the consume and purchase of alcoholic beverage even after said age of majority[6]), regardless of their physical, mental and sexual development as biological adults.[1][7][8] Children generally have fewer rights and responsibilities than adults. They are generally classed as unable to make serious decisions.

Child may also describe a relationship with a parent (such as sons and daughters of any age)[9] or, metaphorically, an authority figure, or signify group membership in a clan, tribe, or religion; it can also signify being strongly affected by a specific time, place, or circumstance, as in "a child of nature" or "a child of the Sixties."[10]

Biological, legal and social definitions

[edit]

Children playing ball games, Roman artwork, 2nd century AD

Children playing ball games, Roman artwork, 2nd century AD

In the biological sciences, a child is usually defined as a person between birth and puberty,[1][2] or between the developmental period of infancy and puberty.[3] Legally, the term child may refer to anyone below the age of majority or some other age limit.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child defines child as, "A human being below the age of 18 years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier."[11] This is ratified by 192 of 194 member countries. The term child may also refer to someone below another legally defined age limit unconnected to the age of majority. In Singapore, for example, a child is legally defined as someone under the age of 14 under the "Children and Young Persons Act" whereas the age of majority is 21.[12][13] In U.S. Immigration Law, a child refers to anyone who is under the age of 21.[14]

Some English definitions of the word child include the fetus (sometimes termed the unborn).[15] In many cultures, a child is considered an adult after undergoing a rite of passage, which may or may not correspond to the time of puberty.

Children generally have fewer rights than adults and are classed as unable to make serious decisions, and legally must always be under the care of a responsible adult or child custody, whether their parents divorce or not.

Developmental stages of childhood

[edit]

Further information: Child development stages and Child development

Early childhood

[edit]

Children playing the violin in a group recital, Ithaca, New York, 2011

Children playing the violin in a group recital, Ithaca, New York, 2011

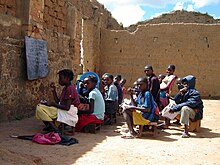

Children in Madagascar, 2011

Children in Madagascar, 2011

Child playing piano, 1984

Child playing piano, 1984

Early childhood follows the infancy stage and begins with toddlerhood when the child begins speaking or taking steps independently.[16][17] While toddlerhood ends around age 3 when the child becomes less dependent on parental assistance for basic needs, early childhood continues approximately until the age of 5 or 6. However, according to the National Association for the Education of Young Children, early childhood also includes infancy. At this stage children are learning through observing, experimenting and communicating with others. Adults supervise and support the development process of the child, which then will lead to the child's autonomy. Also during this stage, a strong emotional bond is created between the child and the care providers. The children also start preschool and kindergarten at this age: and hence their social lives.

Middle childhood

[edit]

Middle childhood begins at around age 7, and ends at around age 9 or 10.[18] Together, early and middle childhood are called formative years. In this middle period, children develop socially and mentally. They are at a stage where they make new friends and gain new skills, which will enable them to become more independent and enhance their individuality. During middle childhood, children enter the school years, where they are presented with a different setting than they are used to. This new setting creates new challenges and faces for children.[19] Upon the entrance of school, mental disorders that would normally not be noticed come to light. Many of these disorders include: autism, dyslexia, dyscalculia, and ADHD.[20]: 303–309  Special education, least restrictive environment, response to intervention and individualized education plans are all specialized plans to help children with disabilities.[20]: 310–311

Middle childhood is the time when children begin to understand responsibility and are beginning to be shaped by their peers and parents. Chores and more responsible decisions come at this time, as do social comparison and social play.[20]: 338  During social play, children learn from and teach each other, often through observation.[21]

Late childhood

[edit]

Main article: Preadolescence

Preadolescence is a stage of human development following early childhood and preceding adolescence. Preadolescence is commonly defined as ages 9–12, ending with the major onset of puberty, with markers such as menarche, spermarche, and the peak of height velocity occurring. These changes usually occur between ages 11 and 14. It may also be defined as the 2-year period before the major onset of puberty.[22] Preadolescence can bring its own challenges and anxieties. Preadolescent children have a different view of the world from younger children in many significant ways. Typically, theirs is a more realistic view of life than the intense, fantasy-oriented world of earliest childhood. Preadolescents have more mature, sensible, realistic thoughts and actions: 'the most "sensible" stage of development...the child is a much less emotional being now.'[23] Preadolescents may well view human relationships differently (e.g. they may notice the flawed, human side of authority figures). Alongside that, they may begin to develop a sense of self-identity, and to have increased feelings of independence: 'may feel an individual, no longer "just one of the family."'[24]

Developmental stages post-childhood

[edit]

Adolescence

[edit]

An adolescent girl, photographed by Paolo Monti

An adolescent girl, photographed by Paolo Monti

Adolescence is usually determined to be between the onset of puberty and legal adulthood: mostly corresponding to the teenage years (13–19). However, puberty usually begins before the teenage years (10—11 for girls and 11—12 for boys). Although biologically a child is a human being between the stages of birth and puberty,[1][2] adolescents are legally considered children, as they tend to lack adult rights and are still required to attend compulsory schooling in many cultures, though this varies. The onset of adolescence brings about various physical, psychological and behavioral changes. The end of adolescence and the beginning of adulthood varies by country and by function, and even within a single nation-state or culture there may be different ages at which an individual is considered to be mature enough to be entrusted by society with certain tasks.

History

[edit]

Main article: History of childhood

Playing Children, by Song dynasty Chinese artist Su Hanchen, c. 1150 AD.

Playing Children, by Song dynasty Chinese artist Su Hanchen, c. 1150 AD.

During the European Renaissance, artistic depictions of children increased dramatically, which did not have much effect on the social attitude toward children, however.[25]

The French historian Philippe Ariès argued that during the 1600s, the concept of childhood began to emerge in Europe,[26] however other historians like Nicholas Orme have challenged this view and argued that childhood has been seen as a separate stage since at least the medieval period.[27] Adults saw children as separate beings, innocent and in need of protection and training by the adults around them. The English philosopher John Locke was particularly influential in defining this new attitude towards children, especially with regard to his theory of the tabula rasa, which considered the mind at birth to be a "blank slate". A corollary of this doctrine was that the mind of the child was born blank, and that it was the duty of the parents to imbue the child with correct notions. During the early period of capitalism, the rise of a large, commercial middle class, mainly in the Protestant countries of the Dutch Republic and England, brought about a new family ideology centred around the upbringing of children. Puritanism stressed the importance of individual salvation and concern for the spiritual welfare of children.[28]

The Age of Innocence c. 1785/8. Reynolds emphasized the natural grace of children in his paintings.

The Age of Innocence c. 1785/8. Reynolds emphasized the natural grace of children in his paintings.

The modern notion of childhood with its own autonomy and goals began to emerge during the 18th-century Enlightenment and the Romantic period that followed it.[29][30] Jean Jacques Rousseau formulated the romantic attitude towards children in his famous 1762 novel Emile: or, On Education. Building on the ideas of John Locke and other 17th-century thinkers, Jean-Jaques Rousseau described childhood as a brief period of sanctuary before people encounter the perils and hardships of adulthood.[29] Sir Joshua Reynolds' extensive children portraiture demonstrated the new enlightened attitudes toward young children. His 1788 painting The Age of Innocence emphasizes the innocence and natural grace of the posing child and soon became a public favourite.[31]

Brazilian princesses Leopoldina (left) and Isabel (center) with an unidentified friend, c. 1860.

Brazilian princesses Leopoldina (left) and Isabel (center) with an unidentified friend, c. 1860.

The idea of childhood as a locus of divinity, purity, and innocence is further expounded upon in William Wordsworth's "Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood", the imagery of which he "fashioned from a complex mix of pastoral aesthetics, pantheistic views of divinity, and an idea of spiritual purity based on an Edenic notion of pastoral innocence infused with Neoplatonic notions of reincarnation".[30] This Romantic conception of childhood, historian Margaret Reeves suggests, has a longer history than generally recognized, with its roots traceable to similarly imaginative constructions of childhood circulating, for example, in the neo-platonic poetry of seventeenth-century metaphysical poet Henry Vaughan (e.g., "The Retreate", 1650; "Childe-hood", 1655). Such views contrasted with the stridently didactic, Calvinist views of infant depravity.

Armenian scouts in 1918

Armenian scouts in 1918

With the onset of industrialisation in England in 1760, the divergence between high-minded romantic ideals of childhood and the reality of the growing magnitude of child exploitation in the workplace, became increasingly apparent. By the late 18th century, British children were specially employed in factories and mines and as chimney sweeps,[33] often working long hours in dangerous jobs for low pay.[34] As the century wore on, the contradiction between the conditions on the ground for poor children and the middle-class notion of childhood as a time of simplicity and innocence led to the first campaigns for the imposition of legal protection for children.

British reformers attacked child labor from the 1830s onward, bolstered by the horrific descriptions of London street life by Charles Dickens.[35] The campaign eventually led to the Factory Acts, which mitigated the exploitation of children at the workplace[33][36]

Modern concepts of childhood

[edit]

Children play in a fountain in a summer evening, Davis, California.

Children play in a fountain in a summer evening, Davis, California.

An old man and his granddaughter in Turkey.

An old man and his granddaughter in Turkey.

Nepalese children playing with cats.

Nepalese children playing with cats.

Harari girls in Ethiopia.

Harari girls in Ethiopia.

The modern attitude to children emerged by the late 19th century; the Victorian middle and upper classes emphasized the role of the family and the sanctity of the child – an attitude that has remained dominant in Western societies ever since.[37] The genre of children's literature took off, with a proliferation of humorous, child-oriented books attuned to the child's imagination. Lewis Carroll's fantasy Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, published in 1865 in England, was a landmark in the genre; regarded as the first "English masterpiece written for children", its publication opened the "First Golden Age" of children's literature.

The latter half of the 19th century saw the introduction of compulsory state schooling of children across Europe, which decisively removed children from the workplace into schools.[38][39]

The market economy of the 19th century enabled the concept of childhood as a time of fun, happiness, and imagination. Factory-made dolls and doll houses delighted the girls and organized sports and activities were played by the boys.[40] The Boy Scouts was founded by Sir Robert Baden-Powell in 1908,[41][42] which provided young boys with outdoor activities aiming at developing character, citizenship, and personal fitness qualities.[43]

In the 20th century, Philippe Ariès, a French historian specializing in medieval history, suggested that childhood was not a natural phenomenon, but a creation of society in his 1960 book Centuries of Childhood. In 1961 he published a study of paintings, gravestones, furniture, and school records, finding that before the 17th century, children were represented as mini-adults.

In 1966, the American philosopher George Boas published the book The Cult of Childhood. Since then, historians have increasingly researched childhood in past times.[44]

In 2006, Hugh Cunningham published the book Invention of Childhood, looking at British childhood from the year 1000, the Middle Ages, to what he refers to as the Post War Period of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.[45]

Childhood evolves and changes as lifestyles change and adult expectations alter. In the modern era, many adults believe that children should not have any worries or work, as life should be happy and trouble-free. Childhood is seen as a mixture of simplicity, innocence, happiness, fun, imagination, and wonder. It is thought of as a time of playing, learning, socializing, exploring, and worrying in a world without much adult interference.[29][30]

A "loss of innocence" is a common concept, and is often seen as an integral part of coming of age. It is usually thought of as an experience or period in a child's life that widens their awareness of evil, pain or the world around them. This theme is demonstrated in the novels To Kill a Mockingbird and Lord of the Flies. The fictional character Peter Pan was the embodiment of a childhood that never ends.[46][47]

Healthy childhoods

[edit]

Role of parents

[edit]

Main article: Parenting

Children's health

[edit]

Further information: Childhood obesity, Childhood immunizations, and List of childhood diseases

Children's health includes the physical, mental and social well-being of children. Maintaining children's health implies offering them healthy foods, insuring they get enough sleep and exercise, and protecting their safety.[48] Children in certain parts of the world often suffer from malnutrition, which is often associated with other conditions, such diarrhea, pneumonia and malaria.[49]

Child protection

[edit]

Further information: Child labor, Child labor laws, Risk aversion, Child abuse, and Protection of Children Act

Child protection, according to UNICEF, refers to "preventing and responding to violence, exploitation and abuse against children – including commercial sexual exploitation, trafficking, child labour and harmful traditional practices, such as female genital mutilation/cutting and child marriage".[50] The Convention on the Rights of the Child protects the fundamental rights of children.

Play

[edit]

Further information: Play (activity), Playground, Imaginary friend, and Childhood secret club

Dancing at Mother of Peace AIDs orphanage, Zimbabwe

Dancing at Mother of Peace AIDs orphanage, Zimbabwe

Play is essential to the cognitive, physical, social, and emotional well-being of children.[51] It offers children opportunities for physical (running, jumping, climbing, etc.), intellectual (social skills, community norms, ethics and general knowledge) and emotional development (empathy, compassion, and friendships). Unstructured play encourages creativity and imagination. Playing and interacting with other children, as well as some adults, provides opportunities for friendships, social interactions, conflicts and resolutions. However, adults tend to (often mistakenly) assume that virtually all children's social activities can be understood as "play" and, furthermore, that children's play activities do not involve much skill or effort.[52][53][54][55]

It is through play that children at a very early age engage and interact in the world around them. Play allows children to create and explore a world they can master, conquering their fears while practicing adult roles, sometimes in conjunction with other children or adult caregivers.[51] Undirected play allows children to learn how to work in groups, to share, to negotiate, to resolve conflicts, and to learn self-advocacy skills. However, when play is controlled by adults, children acquiesce to adult rules and concerns and lose some of the benefits play offers them. This is especially true in developing creativity, leadership, and group skills.[51]

Ralph Hedley, The Tournament, 1898. It depicts poorer boys playing outdoors in a rural part of the Northeast of England.

Ralph Hedley, The Tournament, 1898. It depicts poorer boys playing outdoors in a rural part of the Northeast of England.

Play is considered to be very important to optimal child development that it has been recognized by the United Nations Commission on Human Rights as a right of every child.[11] Children who are being raised in a hurried and pressured style may limit the protective benefits they would gain from child-driven play.[51]

The initiation of play in a classroom setting allows teachers and students to interact through playfulness associated with a learning experience. Therefore, playfulness aids the interactions between adults and children in a learning environment. “Playful Structure” means to combine informal learning with formal learning to produce an effective learning experience for children at a young age.[56]

Even though play is considered to be the most important to optimal child development, the environment affects their play and therefore their development. Poor children confront widespread environmental inequities as they experience less social support, and their parents are less responsive and more authoritarian. Children from low income families are less likely to have access to books and computers which would enhance their development.[57]

Street culture

[edit]

Main articles: Children's street culture and Children's street games

Children in front of a movie theatre, Toronto, 1920s.

Children in front of a movie theatre, Toronto, 1920s.

Children's street culture refers to the cumulative culture created by young children and is sometimes referred to as their secret world. It is most common in children between the ages of seven and twelve. It is strongest in urban working class industrial districts where children are traditionally free to play out in the streets for long periods without supervision. It is invented and largely sustained by children themselves with little adult interference.

Young children's street culture usually takes place on quiet backstreets and pavements, and along routes that venture out into local parks, playgrounds, scrub and wasteland, and to local shops. It often imposes imaginative status on certain sections of the urban realm (local buildings, kerbs, street objects, etc.). Children designate specific areas that serve as informal meeting and relaxation places (see: Sobel, 2001). An urban area that looks faceless or neglected to an adult may have deep 'spirit of place' meanings in to children. Since the advent of indoor distractions such as video games, and television, concerns have been expressed about the vitality – or even the survival – of children's street culture.

Geographies of childhood

[edit]

The geographies of childhood involves how (adult) society perceives the idea of childhood, the many ways adult attitudes and behaviors affect children's lives, including the environment which surrounds children and its implications.[58]

The geographies of childhood is similar in some respects to children's geographies which examines the places and spaces in which children live.[59]

Nature deficit disorder

[edit]

Main article: Nature deficit disorder

Nature Deficit Disorder, a term coined by Richard Louv in his 2005 book Last Child in the Woods, refers to the trend in the United States and Canada towards less time for outdoor play,[60][61] resulting in a wide range of behavioral problems.[62]

With increasing use of cellphones, computers, video games and television, children have more reasons to stay inside rather than outdoors exploring. “The average American child spends 44 hours a week with electronic media”.[63] Research in 2007 has drawn a correlation between the declining number of National Park visits in the U.S. and increasing consumption of electronic media by children.[64] The media has accelerated the trend for children's nature disconnection by deemphasizing views of nature, as in Disney films.[65]

Age of responsibility

[edit]

Further information: Age of consent, Age of majority, Age of criminal responsibility, and Marriageable age

The age at which children are considered responsible for their society-bound actions (e. g. marriage, voting, etc.) has also changed over time,[66] and this is reflected in the way they are treated in courts of law. In Roman times, children were regarded as not culpable for crimes, a position later adopted by the Church. In the 19th century, children younger than seven years old were believed incapable of crime. Children from the age of seven forward were considered responsible for their actions. Therefore, they could face criminal charges, be sent to adult prison, and be punished like adults by whipping, branding or hanging. However, courts at the time would consider the offender's age when deliberating sentencing.[citation needed] Minimum employment age and marriage age also vary. The age limit of voluntary/involuntary military service is also disputed at the international level.[67]

Education

[edit]

Children in an outdoor classroom in Bié, Angola

Children in an outdoor classroom in Bié, Angola

Children seated in a Finnish classroom at the school of Torvinen in Sodankylä, Finland, in the 1920s

Children seated in a Finnish classroom at the school of Torvinen in Sodankylä, Finland, in the 1920s

Main article: Education

Education, in the general sense, refers to the act or process of imparting or acquiring general knowledge, developing the powers of reasoning and judgment, and preparing intellectually for mature life.[68] Formal education most often takes place through schooling. A right to education has been recognized by some governments. At the global level, Article 13 of the United Nations' 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) recognizes the right of everyone to an education.[69] Education is compulsory in most places up to a certain age, but attendance at school may not be, with alternative options such as home-schooling or e-learning being recognized as valid forms of education in certain jurisdictions.

Children in some countries (especially in parts of Africa and Asia) are often kept out of school, or attend only for short periods. Data from UNICEF indicate that in 2011, 57 million children were out of school; and more than 20% of African children have never attended primary school or have left without completing primary education.[70] According to a UN report, warfare is preventing 28 million children worldwide from receiving an education, due to the risk of sexual violence and attacks in schools.[71] Other factors that keep children out of school include poverty, child labor, social attitudes, and long distances to school.[72][73]

Attitudes toward children

[edit]

Group of breaker boys in Pittston, Pennsylvania, 1911. Child labor was widespread until the early 20th century. In the 21st century, child labor rates are highest in Africa.

Group of breaker boys in Pittston, Pennsylvania, 1911. Child labor was widespread until the early 20th century. In the 21st century, child labor rates are highest in Africa.

Social attitudes toward children differ around the world in various cultures and change over time. A 1988 study on European attitudes toward the centrality of children found that Italy was more child-centric and the Netherlands less child-centric, with other countries, such as Austria, Great Britain, Ireland and West Germany falling in between.[74]

Child marriage

[edit]

In 2013, child marriage rates of female children under the age of 18 reached 75% in Niger, 68% in Central African Republic and Chad, 66% in Bangladesh, and 47% in India.[75] According to a 2019 UNICEF report on child marriage, 37% of females were married before the age of 18 in sub-Saharan Africa, followed by South Asia at 30%. Lower levels were found in Latin America and Caribbean (25%), the Middle East and North Africa (18%), and Eastern Europe and Central Asia (11%), while rates in Western Europe and North America were minimal.[76] Child marriage is more prevalent with girls, but also involves boys. A 2018 study in the journal Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies found that, worldwide, 4.5% of males are married before age 18, with the Central African Republic having the highest average rate at 27.9%.[77]

Fertility and number of children per woman

[edit]

Before contraception became widely available in the 20th century, women had little choice other than abstinence or having often many children. In fact, current population growth concerns have only become possible with drastically reduced child mortality and sustained fertility. In 2017 the global total fertility rate was estimated to be 2.37 children per woman,[78] adding about 80 million people to the world population per year. In order to measure the total number of children, scientists often prefer the completed cohort fertility at age 50 years (CCF50).[78] Although the number of children is also influenced by cultural norms, religion, peer pressure and other social factors, the CCF50 appears to be most heavily dependent on the educational level of women, ranging from 5–8 children in women without education to less than 2 in women with 12 or more years of education.[78]

Issues

[edit]

Emergencies and conflicts

[edit]

See also: Declaration on the Protection of Women and Children in Emergency and Armed Conflict, Children in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, Save the Children, Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies, Military use of children, Trafficking of children, International child abduction, and Refugee children

Emergencies and conflicts pose detrimental risks to the health, safety, and well-being of children. There are many different kinds of conflicts and emergencies, e.g. wars and natural disasters. As of 2010 approximately 13 million children are displaced by armed conflicts and violence around the world.[79] Where violent conflicts are the norm, the lives of young children are significantly disrupted and their families have great difficulty in offering the sensitive and consistent care that young children need for their healthy development.[79] Studies on the effect of emergencies and conflict on the physical and mental health of children between birth and 8 years old show that where the disaster is natural, the rate of PTSD occurs in anywhere from 3 to 87 percent of affected children.[80] However, rates of PTSD for children living in chronic conflict conditions varies from 15 to 50 percent.[81][82]

Child protection

[edit]

This section is an excerpt from Child protection.[edit]

Child protection (also called child welfare) is the safeguarding of children from violence, exploitation, abuse, abandonment, and neglect.[83][84][85][86] It involves identifying signs of potential harm. This includes responding to allegations or suspicions of abuse, providing support and services to protect children, and holding those who have harmed them accountable.[87]

The primary goal of child protection is to ensure that all children are safe and free from harm or danger.[86][88] Child protection also works to prevent future harm by creating policies and systems that identify and respond to risks before they lead to harm.[89]

In order to achieve these goals, research suggests that child protection services should be provided in a holistic way.[90][91][92] This means taking into account the social, economic, cultural, psychological, and environmental factors that can contribute to the risk of harm for individual children and their families. Collaboration across sectors and disciplines to create a comprehensive system of support and safety for children is required.[93][94]

It is the responsibility of individuals, organizations, and governments to ensure that children are protected from harm and their rights are respected.[95] This includes providing a safe environment for children to grow and develop, protecting them from physical, emotional and sexual abuse, and ensuring they have access to education, healthcare, and resources to fulfill their basic needs.[96]

Child protection systems are a set of services, usually government-run, designed to protect children and young people who are underage and to encourage family stability. UNICEF defines[97] a 'child protection system' as:

"The set of laws, policies, regulations and services needed across all social sectors – especially social welfare, education, health, security and justice – to support prevention and response to protection-related risks. These systems are part of social protection, and extend beyond it. At the level of prevention, their aim includes supporting and strengthening families to reduce social exclusion, and to lower the risk of separation, violence and exploitation. Responsibilities are often spread across government agencies, with services delivered by local authorities, non-State providers, and community groups, making coordination between sectors and levels, including routine referral systems etc.., a necessary component of effective child protection systems."

— United Nations Economic and Social Council (2008), UNICEF Child Protection Strategy, E/ICEF/2008/5/Rev.1, par. 12–13.

Under Article 19 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, a 'child protection system' provides for the protection of children in and out of the home. One of the ways this can be enabled is through the provision of quality education, the fourth of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, in addition to other child protection systems. Some literature argues that child protection begins at conception; even how the conception took place can affect the child's development.[98]

Child abuse and child labor

[edit]

Protection of children from abuse is considered an important contemporary goal. This includes protecting children from exploitation such as child labor, child trafficking and child selling, child sexual abuse, including child prostitution and child pornography, military use of children, and child laundering in illegal adoptions. There exist several international instruments for these purposes, such as:

- Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention

- Minimum Age Convention, 1973

- Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography

- Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse

- Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict

- Hague Adoption Convention

Climate change

[edit]

This section is an excerpt from Climate change and children.[edit]

A child at a climate demonstration in Juneau, Alaska

A child at a climate demonstration in Juneau, Alaska

Children are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change than adults. The World Health Organization estimated that 88% of the existing global burden of disease caused by climate change affects children under five years of age.[99] A Lancet review on health and climate change lists children as the worst-affected category by climate change.[100] Children under 14 are 44 percent more likely to die from environmental factors,[101] and those in urban areas are disproportionately impacted by lower air quality and overcrowding.[102]

Children are physically more vulnerable to climate change in all its forms.[103] Climate change affects the physical health of children and their well-being. Prevailing inequalities, between and within countries, determine how climate change impacts children.[104] Children often have no voice in terms of global responses to climate change.[103]

People living in low-income countries experience a higher burden of disease and are less capable of coping with climate change-related threats.

[105] Nearly every child in the world is at risk from climate change and pollution, while almost half are at extreme risk.

[106]

Health

[edit]

Child mortality

[edit]

Main articles: Child mortality and Infant mortality

World infant mortality rates in 2012.[107]

World infant mortality rates in 2012.[107]

During the early 17th century in England, about two-thirds of all children died before the age of four.[108] During the Industrial Revolution, the life expectancy of children increased dramatically.[109] This has continued in England, and in the 21st century child mortality rates have fallen across the world. About 12.6 million under-five infants died worldwide in 1990, which declined to 6.6 million in 2012. The infant mortality rate dropped from 90 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990, to 48 in 2012. The highest average infant mortality rates are in sub-Saharan Africa, at 98 deaths per 1,000 live births – over double the world's average.[107]

See also

[edit]

This audio file was created from a revision of this article dated 24 June 2008 (2008-06-24), and does not reflect subsequent edits.

- Outline of childhood

- Child slavery

- Childlessness

- Depression in childhood and adolescence

- One-child policy

- Religion and children

- Youth rights

- Archaeology of childhood

Sources

[edit]

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Investing against Evidence: The Global State of Early Childhood Care and Education​, 118–125, Marope PT, Kaga Y, UNESCO. UNESCO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Investing against Evidence: The Global State of Early Childhood Care and Education​, 118–125, Marope PT, Kaga Y, UNESCO. UNESCO. This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Creating sustainable futures for all; Global education monitoring report, 2016; Gender review​, 20, UNESCO, UNESCO. UNESCO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from Creating sustainable futures for all; Global education monitoring report, 2016; Gender review​, 20, UNESCO, UNESCO. UNESCO.

References

[edit]

- ^ a b c d

"Child". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ a b c O'Toole, MT (2013). Mosby's Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing & Health Professions. St. Louis MO: Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-323-07403-2. OCLC 800721165. Wikidata Q19573070.

- ^ a b Rathus SA (2013). Childhood and Adolescence: Voyages in Development. Cengage Learning. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-285-67759-0.

- ^ "Child". OED.com. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "Child". Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "When Is It Legal For Minors To Drink?". Alcohol.org. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ "Children and the law". NSPCC Learning. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ "23.8: Adulthood". LibreTexts - Biology. 31 December 2018.

A person may be physically mature and a biological adult by age 16 or so, but not defined as an adult by law until older ages. For example, in the U.S., you cannot join the armed forces or vote until age 18, and you cannot take on many legal and financial responsibilities until age 21.

- ^ "For example, the US Social Security department specifically defines an adult child as being over 18". Ssa.gov. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "American Heritage Dictionary". 7 December 2007. Archived from the original on 29 December 2007.

- ^ a b "Convention on the Rights of the Child" (PDF). General Assembly Resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989. The Policy Press, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2010.

- ^ "Children and Young Persons Act". Singapore Statutes Online. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Proposal to lower the Age of Contractual Capacity from 21 years to 18 years, and the Civil Law (Amendment) Bill". Singapore: Ministry of Law. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ "8 U.S. Code § 1101 - Definitions". LII / Legal Information Institute.

- ^ See Shorter Oxford English Dictionary 397 (6th ed. 2007), which's first definition is "A fetus; an infant;...". See also ‘The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary: Complete Text Reproduced Micrographically’, Vol. I (Oxford University Press, Oxford 1971): 396, which defines it as: ‘The unborn or newly born human being; foetus, infant’.

- ^ Alam, Gajanafar (2014). Population and Society. K.K. Publications. ISBN 978-8178441986.

- ^ Purdy ER (18 January 2019). "Infant and toddler development". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "Development In Middle Childhood".

- ^ Collins WA, et al. (National Research Council (US) Panel to Review the Status of Basic Research on School-Age Children) (1984). Development during Middle Childhood. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press (US). doi:10.17226/56. ISBN 978-0-309-03478-4. PMID 25032422.

- ^ a b c Berger K (2017). The Developing Person through the Lifespan. Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1-319-01587-9.

- ^ Konner M (2010). The Evolution of Childhood. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 512–513. ISBN 978-0-674-04566-8.

- ^ "APA Dictionary of Psychology".

- ^ Mavis Klein, Okay Parenting (1991) p. 13 and p. 78

- ^ E. Fenwick/T. Smith, Adolescence (London 1993) p. 29

- ^ Pollock LA (2000). Forgotten children : parent-child relations from 1500 to 1900. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-25009-2. OCLC 255923951.

- ^ Ariès P (1960). Centuries of Childhood.

- ^ Orme, Nicholas (2001). Medieval Children. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08541-9.

- ^ Fox VC (April 1996). "Poor Children's Rights in Early Modern England". The Journal of Psychohistory. 23 (3): 286–306.

- ^ a b c Cohen D (1993). The development of play (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-134-86782-0.

- ^ a b c Reeves M (2018). "'A Prospect of Flowers', Concepts of Childhood and Female Youth in Seventeenth-Century British Culture". In Cohen ES, Reeves M (eds.). The Youth of Early Modern Women. Amsterdam University Press. p. 40. doi:10.2307/j.ctv8pzd5z. ISBN 978-90-485-3498-2. JSTOR j.ctv8pzd5z. S2CID 189343394. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Postle, Martin. (2005) "The Age of Innocence" Child Portraiture in Georgian Art and Society", in Pictures of Innocence: Portraits of Children from Hogarth to Lawrence. Bath: Holburne Museum of Art, pp. 7–8. ISBN 0903679094

- ^ a b Del Col L (September 1930). "The Life of the Industrial Worker in Ninteenth-Century [sic] England — Evidence Given Before the Sadler Committee (1831–1832)". In Scott JF, Baltzly A (eds.). Readings in European History. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- ^ Daniels B. "Poverty and Families in the Victorian Era". hiddenlives.org.

- ^ Malkovich A (2013). Charles Dickens and the Victorian child : romanticizing and socializing the imperfect child. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-07425-8.

- ^ "The Factory and Workshop Act, 1901". British Medical Journal. 2 (2139): 1871–1872. December 1901. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2139.1871. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 2507680. PMID 20759953.

- ^ Jordan TE (1998). Victorian child savers and their culture : a thematic evaluation. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-8289-0. OCLC 39465039.

- ^ Sagarra, Eda. (1977). A Social History of Germany 1648–1914, pp. 275–84

- ^ Weber, Eugen. (1976). Peasants into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France, 1870–1914, pp. 303–38

- ^ Chudacoff HP (2007). Children at Play: An American History. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1665-6.

- ^ Woolgar B, La Riviere S (2002). Why Brownsea? The Beginnings of Scouting. Brownsea Island Scout and Guide Management Committee.

- ^ Hillcourt, William (1964). Baden-Powell; the two lives of a hero. New York: Putnam. ISBN 978-0839535942. OCLC 1338723.

- ^ Boehmer E (2004). Notes to 2004 edition of Scouting for Boys. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Ulbricht J (November 2005). "J.C. Holz Revisited: From Modernism to Visual Culture". Art Education. 58 (6): 12–17. doi:10.1080/00043125.2005.11651564. ISSN 0004-3125. S2CID 190482412.

- ^ Cunningham H (July 2016). "The Growth of Leisure in the Early Industrial Revolution, c. 1780–c. 1840". Leisure in the Industrial Revolution. Routledge. pp. 15–56. doi:10.4324/9781315637679-2. ISBN 978-1-315-63767-9.

- ^ Bloom, Harold. "Major themes in Lord of the Flies" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2019.

- ^ Barrie, J. M. Peter Pan. Hodder & Stoughton, 1928, Act V, Scene 2.

- ^ "Children's Health". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- ^ Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Blössner M, Black RE (July 2004). "Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 80 (1): 193–198. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.1.193. PMID 15213048.

- ^ "What is child Protection?" (PDF). The United Nations Children’s Fund (UniCeF). May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d Ginsburg KR (January 2007). "The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds". Pediatrics. 119 (1): 182–191. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2697. PMID 17200287. S2CID 54617427.

- ^ Björk-Willén P, Cromdal J (2009). "When education seeps into 'free play': How preschool children accomplish multilingual education". Journal of Pragmatics. 41 (8): 1493–1518. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2007.06.006.

- ^ Cromdal J (2001). "Can I be with?: Negotiating play entry in a bilingual school". Journal of Pragmatics. 33 (4): 515–543. doi:10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00131-9.

- ^ Butler CW (2008). Talk and social interaction in the playground. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-7416-0.

- ^ Cromdal J (2009). "Childhood and social interaction in everyday life: Introduction to the special issue". Journal of Pragmatics. 41 (8): 1473–76. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2007.03.008.

- ^ Walsh G, Sproule L, McGuinness C, Trew K (July 2011). "Playful structure: a novel image of early years pedagogy for primary school classrooms". Early Years. 31 (2): 107–119. doi:10.1080/09575146.2011.579070. S2CID 154926596.

- ^ Evans GW (2004). "The environment of childhood poverty". The American Psychologist. 59 (2): 77–92. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77. PMID 14992634.

- ^ Disney, Tom (2018). Geographies of Children and Childhood. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199874002-0193.

- ^ Holloway SL (2004). Holloway SL, Valentine G (eds.). Children's Geographies. doi:10.4324/9780203017524. ISBN 978-0-203-01752-4.

- ^ Gardner M (29 June 2006). "For more children, less time for outdoor play: Busy schedules, less open space, more safety fears, and lure of the Web keep kids inside". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ Swanbrow D. "U.S. children and teens spend more time on academics". The University Record Online. The University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ Burak T. "Are your kids really spending enough time outdoors? Getting up close with nature opens a child's eyes to the wonders of the world, with a bounty of health benefits". Canadian Living. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012.

- ^ O'Driscoll B. "Outside Agitators". Pittsburgh City Paper. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011.

- ^ Pergams OR, Zaradic PA (September 2006). "Is love of nature in the US becoming love of electronic media? 16-year downtrend in national park visits explained by watching movies, playing video games, internet use, and oil prices". Journal of Environmental Management. 80 (4): 387–393. Bibcode:2006JEnvM..80..387P. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.02.001. PMID 16580127.

- ^ Prévot-Julliard AC, Julliard R, Clayton S (August 2015). "Historical evidence for nature disconnection in a 70-year time series of Disney animated films". Public Understanding of Science. 24 (6): 672–680. doi:10.1177/0963662513519042. PMID 24519887. S2CID 43190714.

- ^ RJ, Raawat (9 December 2021). "बचà¥à¤šà¥‡ चà¥à¤¨à¥Œà¤¤à¤¿à¤¯à¥‹à¤‚ का जवाब दे सकते हैं – द समठà¤à¤¨.जी.ओ." Navbharat Times Reader's Blog (in Hindi). Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Yun S (2014). "BreakingImaginary Barriers: Obligations of Armed Non-State Actors Under General Human Rights Law – The Case of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child". Journal of International Humanitarian Legal Studies. 5 (1–2): 213–257. doi:10.1163/18781527-00501008. S2CID 153558830. SSRN 2556825.

- ^ "Define Education". Dictionary.com. Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ ICESCR, Article 13.1

- ^ "Out-of-School Children Initiative | Basic education and gender equality". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 6 August 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "BBC News - Unesco: Conflict robs 28 million children of education". Bbc.co.uk. 1 March 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "UK | Education | Barriers to getting an education". BBC News. 10 April 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Melik J (11 October 2012). "Africa gold rush lures children out of school". Bbc.com – BBC News. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Jones RK, Brayfield A (June 1997). "Life's greatest joy?: European attitudes toward the centrality of children". Social Forces. 75 (4): 1239–1269. doi:10.1093/sf/75.4.1239.

- ^ "Child brides around the world sold off like cattle". USA Today. Associated Press. 8 March 2013. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013.

- ^ "Child marriage". UNICEF DATA. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Gastón CM, Misunas C, Cappa C (3 July 2019). "Child marriage among boys: a global overview of available data". Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 14 (3): 219–228. doi:10.1080/17450128.2019.1566584. ISSN 1745-0128.

- ^ a b c Vollset SE, Goren E, Yuan CW, Cao J, Smith AE, Hsiao T, et al. (October 2020). "Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study". Lancet. 396 (10258): 1285–1306. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30677-2. PMC 7561721. PMID 32679112.

- ^ a b UNICEF (2010). The State of the World's Children Report, Special Edition (PDF). New York: UNICEF. ISBN 978-92-806-4445-6.

- ^ Shannon MP, Lonigan CJ, Finch AJ, Taylor CM (January 1994). "Children exposed to disaster: I. Epidemiology of post-traumatic symptoms and symptom profiles". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 33 (1): 80–93. doi:10.1097/00004583-199401000-00012. PMID 8138525.

- ^ De Jong JT (2002). Trauma, War, and Violence: Public Mental Health in Socio Cultural Context. New York: Kluwer. ISBN 978-0-306-47675-4.

- ^ Marope PT, Kaga Y (2015). Investing against Evidence: The Global State of Early Childhood Care and Education (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. pp. 118–125. ISBN 978-92-3-100113-0.

- ^ Katz, Ilan; Katz, Carmit; Andresen, Sabine; Bérubé, Annie; Collin-Vezina, Delphine; Fallon, Barbara; Fouché, Ansie; Haffejee, Sadiyya; Masrawa, Nadia; Muñoz, Pablo; Priolo Filho, Sidnei R.; Tarabulsy, George; Truter, Elmien; Varela, Natalia; Wekerle, Christine (June 2021). "Child maltreatment reports and Child Protection Service responses during COVID-19: Knowledge exchange among Australia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Germany, Israel, and South Africa". Child Abuse & Neglect. 116 (Pt 2): 105078. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105078. ISSN 0145-2134. PMC 8446926. PMID 33931238.

- ^ Oates, Kim (July 2013). "Medical dimensions of child abuse and neglect". Child Abuse & Neglect. 37 (7): 427–429. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.05.004. ISSN 0145-2134. PMID 23790510.

- ^ Southall, David; MacDonald, Rhona (1 November 2013). "Protecting children from abuse: a neglected but crucial priority for the international child health agenda". Paediatrics and International Child Health. 33 (4): 199–206. doi:10.1179/2046905513Y.0000000097. ISSN 2046-9047. PMID 24070186. S2CID 29250788.

- ^ a b Barth, R.P. (October 1999). "After Safety, What is the Goal of Child Welfare Services: Permanency, Family Continuity or Social Benefit?". International Journal of Social Welfare. 8 (4): 244–252. doi:10.1111/1468-2397.00091. ISSN 1369-6866.

- ^ Child Custody & Domestic Violence: A Call for Safety and Accountability. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc. 2003. doi:10.4135/9781452231730. ISBN 978-0-7619-1826-4.

- ^ Editorial team, Collective (11 September 2008). "WHO Regional Office for Europe and UNAIDS report on progress since the Dublin Declaration". Eurosurveillance. 13 (37). doi:10.2807/ese.13.37.18981-en. ISSN 1560-7917. PMID 18801311.

- ^ Nixon, Kendra L.; Tutty, Leslie M.; Weaver-Dunlop, Gillian; Walsh, Christine A. (December 2007). "Do good intentions beget good policy? A review of child protection policies to address intimate partner violence". Children and Youth Services Review. 29 (12): 1469–1486. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.09.007. ISSN 0190-7409.

- ^ Holland, S. (1 January 2004). "Liberty and Respect in Child Protection". British Journal of Social Work. 34 (1): 21–36. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bch003. ISSN 0045-3102.

- ^ Wulcyzn, Fred; Daro, Deborah; Fluke, John; Gregson, Kendra (2010). "Adapting a Systems Approach to Child Protection in a Cultural Context: Key Concepts and Considerations". PsycEXTRA Dataset. doi:10.1037/e516652013-176.

- ^ Léveillé, Sophie; Chamberland, Claire (1 July 2010). "Toward a general model for child welfare and protection services: A meta-evaluation of international experiences regarding the adoption of the Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and Their Families (FACNF)". Children and Youth Services Review. 32 (7): 929–944. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.03.009. ISSN 0190-7409.

- ^ Winkworth, Gail; White, Michael (March 2011). "Australia's Children 'Safe and Well'?1 Collaborating with Purpose Across Commonwealth Family Relationship and State Child Protection Systems: Australia's Children 'Safe and Well'". Australian Journal of Public Administration. 70 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8500.2010.00706.x.

- ^ Wulcyzn, Fred; Daro, Deborah; Fluke, John; Gregson, Kendra (2010). "Adapting a Systems Approach to Child Protection in a Cultural Context: Key Concepts and Considerations". PsycEXTRA Dataset. doi:10.1037/e516652013-176.

- ^ Howe, R. Brian; Covell, Katherine (July 2010). "Miseducating children about their rights". Education, Citizenship and Social Justice. 5 (2): 91–102. doi:10.1177/1746197910370724. ISSN 1746-1979. S2CID 145540907.

- ^ "Child protection". www.unicef.org. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ "Economic and Social Council" (PDF). UNICEF. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ "Protecting Children from Violence: Historical Roots and Emerging Trends", Protecting Children from Violence, Psychology Press, pp. 21–32, 13 September 2010, doi:10.4324/9780203852927-8, ISBN 978-0-203-85292-7

- ^ Anderko, Laura; Chalupka, Stephanie; Du, Maritha; Hauptman, Marissa (January 2020). "Climate changes reproductive and children's health: a review of risks, exposures, and impacts". Pediatric Research. 87 (2): 414–419. doi:10.1038/s41390-019-0654-7. ISSN 1530-0447. PMID 31731287.

- ^ Watts, Nick; Amann, Markus; Arnell, Nigel; Ayeb-Karlsson, Sonja; Belesova, Kristine; Boykoff, Maxwell; Byass, Peter; Cai, Wenjia; Campbell-Lendrum, Diarmid; Capstick, Stuart; Chambers, Jonathan (16 November 2019). "The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate". Lancet. 394 (10211): 1836–1878. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32596-6. hdl:10871/40583. ISSN 1474-547X. PMID 31733928. S2CID 207976337. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Bartlett, Sheridan (2008). "Climate change and urban children: Impacts and implications for adaptation in low- and middle-income countries". Environment and Urbanization. 20 (2): 501–519. Bibcode:2008EnUrb..20..501B. doi:10.1177/0956247808096125. S2CID 55860349.

- ^ "WHO | The global burden of disease: 2004 update". WHO. Archived from the original on 24 March 2009.

- ^ a b Currie, Janet; Deschênes, Olivier (2016). "Children and Climate Change: Introducing the Issue". The Future of Children. 26 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1353/foc.2016.0000. ISSN 1054-8289. JSTOR 43755227. S2CID 77559783. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Helldén, Daniel; Andersson, Camilla; Nilsson, Maria; Ebi, Kristie L.; Friberg, Peter; Alfvén, Tobias (1 March 2021). "Climate change and child health: a scoping review and an expanded conceptual framework". The Lancet Planetary Health. 5 (3): e164 – e175. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30274-6. ISSN 2542-5196. PMID 33713617.

- ^ "Unless we act now: The impact of climate change on children". www.unicef.org. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (20 August 2021). "A billion children at 'extreme risk' from climate impacts – Unicef". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Infant Mortality Rates in 2012" (PDF). UNICEF. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014.

- ^ Rorabaugh WJ, Critchlow DT, Baker PC (2004). America's promise: a concise history of the United States (Volume 1: To 1877). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-7425-1189-7.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kumar K (29 October 2020). "Modernization – Population Change". Encyclopædia Britannica.

Further reading

[edit]

- Cook, Daniel Thomas. The moral project of childhood: Motherhood, material life, and early children's consumer culture (NYU Press, 2020). online book see also online review

- Fawcett, Barbara, Brid Featherstone, and Jim Goddard. Contemporary child care policy and practice (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017) online

- Hutchison, Elizabeth D., and Leanne W. Charlesworth. "Securing the welfare of children: Policies past, present, and future." Families in Society 81.6 (2000): 576–585.

- Fass, Paula S. The end of American childhood: A history of parenting from life on the frontier to the managed child (Princeton University Press, 2016).

- Fass, Paula S. ed. The Routledge History of Childhood in the Western World (2012) online

- Klass, Perri. The Best Medicine: How Science and Public Health Gave Children a Future (WW Norton & Company, 2020) online

- Michail, Samia. "Understanding school responses to students’ challenging behaviour: A review of literature." Improving schools 14.2 (2011): 156–171. online

- Sorin, Reesa. Changing images of childhood: Reconceptualising early childhood practice (Faculty of Education, University of Melbourne, 2005) online.

- Sorin, Reesa. "Childhood through the eyes of the child and parent." Journal of Australian Research in Early Childhood Education 14.1 (2007). online

- Vissing, Yvonne. "History of Children’s Human Rights in the USA." in Children's Human Rights in the USA: Challenges and Opportunities (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023) pp. 181–212.

- Yuen, Francis K.O. Social work practice with children and families: a family health approach (Routledge, 2014) online.

| Preceded by

Toddlerhood

|

Stages of human development

Childhood |

Succeeded by

Preadolescence

|

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Children.

Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article "Child".

Family

| |

- History

- Household

- Nuclear family

- Extended family

- Conjugal family

- Immediate family

- Matrifocal family

|

| First-degree relatives |

|

| Second-degree relatives |

- Grandparent

- Grandchild

- Uncle/Aunt

- Niece and nephew

|

| Third-degree relatives |

- Great-grandparent

- Great-grandchild

- Great-uncle/Great-aunt

- Cousin

|

| Family-in-law |

- Spouse

- Parent-in-law

- Sibling-in-law

- Child-in-law

- daughter-in-law

- son-in-law

|

| Stepfamily |

- Stepparent

- Stepchild

- Stepsibling

|

| Kinship terminology |

- Kinship

- Australian Aboriginal kinship

- Adoption

- Affinity

- Consanguinity

- Disownment

- Divorce

- Estrangement

- Family of choice

- Fictive kinship

- Marriage

- Nurture kinship

- Chinese kinship

- Hawaiian kinship

- Sudanese kinship

- Eskimo kinship

- Iroquois kinship

- Crow kinship

- Omaha kinship

|

Genealogy

and lineage |

- Bilateral descent

- Common ancestor

- Family name

- Heirloom

- Heredity

- Inheritance

- Lineal descendant

- collateral descent

- Matrilineality

- Patrilineality

- Progenitor

- Clan

- Royal descent

| Family trees |

- Pedigree chart

- Genogram

- Ahnentafel

- Genealogical numbering systems

- Seize quartiers

- Quarters of nobility

|

|

| Relationships |

- Agape (parental love)

- Eros (marital love)

- Philia (brotherly love)

- Storge (familial love)

- Filial piety

- Polyfidelity

|

| Holidays |

- Mother's Day

- Father's Day

- Father–Daughter Day

- Siblings Day

- National Grandparents Day

- Parents' Day

- Children's Day

- Family Day

- American Family Day

- International Day of Families

- National Family Week

- National Adoption Day

|

| Related |

- Single parent

- Wedding anniversary

- Godparent

- Birth order

- Only child

- Middle child syndrome

- Sociology of the family

- Museum of Motherhood

- Astronaut family

- Dysfunctional family

- Domestic violence

- Incest

- Sibling abuse

- Sibling estrangement

- Sibling rivalry

|

Development of the human body

| |

| Before birth |

- Development

- Zygote

- Embryo

- Fetus

- Gestational age

|

| Birth and after |

- Birth

- Child development

- Adult development

- Ageing

- Senescence

- Death

|

| Phases |

- Early years

- Infant

- Toddler

- Early childhood

- Childhood

- Youth

- Preadolescence

- Adolescence

- Emerging adulthood

- Adulthood

- Young adult

- Middle adult

- Elder adult

- Dying

|

| Social and legal |

|

Authority control databases  |

| National |

- United States

- France

- BnF data

- Spain

- Latvia

- Sweden

- Israel

|

| Other |

- NARA

- Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine

|